When I was a young student I mostly disliked science. The only branch of that distinguished area of study that interested me was chemistry. There was a certain magic about the periodic table that tickled my fancy. At one time I might have considered a major in chemical engineering. It would have combined my love of mathematics with a deep interest in the chemistry of our world. Unfortunately the other branches of science held little sway over me, particularly anything dealing with discussions of the earth. Spending time learning about the earth’s composition held no interest as far as I was concerned.

When I was a young student I mostly disliked science. The only branch of that distinguished area of study that interested me was chemistry. There was a certain magic about the periodic table that tickled my fancy. At one time I might have considered a major in chemical engineering. It would have combined my love of mathematics with a deep interest in the chemistry of our world. Unfortunately the other branches of science held little sway over me, particularly anything dealing with discussions of the earth. Spending time learning about the earth’s composition held no interest as far as I was concerned.

There is a certain irony in my distaste for all things geophysical because one of my all time favorite uncles was a geologist and I tended to adore anything associated with him. He was a kind of idol to me and when I examined the rocks and minerals that he collected I listened with intense interest to his “lectures.” He told me where he had found them and how they had been formed and I was transfixed even though I was quite young, a pre-schooler, when he tutored me on such things. My hero worship of him extended to the point of thinking that his every utterance was earth shattering. Unfortunately I lost his influence along with my interest in the science of our home planet when he died of cancer when he was still in his twenties and I was only five.

A psychologist might suggest that my future loathing of geology was really a deep seated psychological reaction to his death. They might be on to something because I did indeed love him to the point of hanging on his every word. When he was gone I had no more reason to want to know more about the way things work in the world of our big blue planet. Instead I found myself barely able to pay attention to discussions of what lies beneath the crust of the earth on which we work and play. Thank goodness there are people like my uncle who demand to know more and not too many like me. It is from their work that we form theories that guide us to better living.

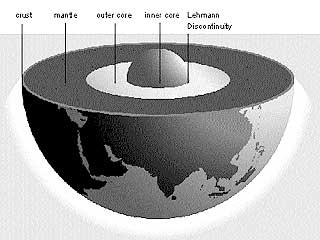

Over time I have grown to have a much higher level of curiosity about things than when I was young. I especially love waking up each morning and checking the Google icon to see if it has changed and to find out why. Today I found a strange representation that I at first thought to be a coconut split in half. It was in reality a depiction of the earth opened up to show its inner core. It’s purpose was to note that today would have been the birthday of Inge Lehmann. Of course I had to Google her name to find out just who she was. What I learned was fascinating on many different levels which I suppose is a kind of pun given what she did.

Inge was a brilliant woman who was born in Denmark at a time when the world still believed that girls had little to offer beyond duties as wives and mothers. She studied mathematics and earned a degree but quickly learned that the pathway to interesting careers is often difficult for those of the female variety. She found work crunching numbers at an insurance company, a job that paid the bills but little else. Inge’s desire to accomplish something more led her to earn an advanced degree which widened her horizons. She found a job that used her skills in the field of seismology. She loved what she was doing and little by little learned more and more until she was an expert and someone whose ideas about geophysics were taken to heart.

Before the nineteen twenties the standard theory of the interior of the earth was that beneath its center was a huge molten mass. Seismologists used this widely accepted fact as an explanation for the reality that once the waves of an earthquake traveled through the center of the earth the energy was absorbed and could no longer be measured. Inge noticed that in an earthquake that struck New Zealand there were tiny measurable waves that somehow got through the center. If the core of the earth were entirely molten this should not have happened. The fact that scientists had received some faint measures bothered her to the point of obsession. She was determined to find out how this may have happened. She literally studied the numbers from the earthquake day and night, mulling over them and carrying them with her wherever she went. Eventually she developed a unique theory and asserted that the existing model of the earth was incorrect. She postulated that much of the center of the earth was indeed molten but that at the very core there was a small but significant solid sphere. Her thesis created a seismic change in the world of geophysics!

We still struggle with both predicting and studying earthquakes but we know far more about what causes such phenomena and what happens during the quakes than ever before. Our measurements have become more and more accurate over time and the work of Inge Lehmann has been crucial in our study of the earth. Had she lived to see today’s Google icon she would have been one hundred twenty seven years old. As it is she came close to being here for the celebration. She had already reached the age of one hundred four when she died.

Inge Lehmann was a pioneer for women. She worked at a time when the vast majority of ladies stayed at home. She earned advanced degrees when few females even had high school diplomas. She entered a field of work once thought to be the exclusive domain of men. Somehow she rose above all of the roadblocks that must have stood in her way and focused on becoming so well versed in her field of endeavor that when she proposed her theory her male peers listened. Hers was an elegantly simple explanation that literally changed the way we view the world and she conceived of it by applying the mathematics that she so loved and understood.

My students would often ask me when they were ever going to use the theorems and algorithms that I taught them. I did my best to explain just how math is an underpinning of science, music, economics, business, architecture, and even something as simple as designing a recipe for cooking. Like that deep core of our earth mathematics is at the center of our learning. It has even been used to explain the anatomy of language in Transformational Grammar. There is something quite beautiful about the ways in which numbers and statistics and measurements all come together each and every day to explain how things work. Perhaps if I had better understood the linkages between mathematics and science I might have followed a different career path when I was searching for an occupation so many decades ago. As it is my attempts to enlighten my students has lit my own torch of knowledge and I am all the better for the experience.

They say that we have the process of learning all mixed up. When we are very young we are so curious that we have to be watched lest we get ourselves in trouble. Somewhere along the way we tend to lose the enthusiasm that we once possessed. We almost have to be pushed to want to learn. Our growing bodies and minds have so many distractions that we have a difficult time focusing. The lot of most teenagers is to be utterly confused about themselves and about the world around them. As we mature things settle down and we rediscover the beauty of learning. We revisit books that we once reviled and realize just how brilliant they are. We long to know our history and to understand how every aspect of our existence operates. We become students again only this time we find great excitement in our discoveries just as small children do. We love the idea of learning something new every day.

I so admire those who like Inge Lehmann who have an impact that goes beyond the limitations of their immediate environment. We humans are an amazing bunch. It is incredible the way we have insisted on finding explanations for everything that we see and hear and touch and taste. Starting with the simplicity of our senses we explore our universe and in learning more and more about it improve life for everyone. Science and mathematics are in point of fact as lovely as a Shakespearean sonnet. There is a kind of music in the explanations of how everything works.